Free trade was never supposed to be the end-game

With the dust settling on tariffs, it is opportune to take a moment to consider the sheer scale of change ushered in by Trump on global trade since 2016, and especially with recent events. Trump’s policy is often confused by a vast amount of ‘noise’, which tends to undermine even his own news cycle (see the recent Iran nuclear facility bombing, for instance). Which is a shame, because he has almost entirely remade the landscape, and whether one supports or opposes the theory behind it, it seems irrevocable.

There have been two major components of this earthquake. First, Trump has instated and effectively normalised a global 10% tariff on all US imports, regardless of origin. As noted elsewhere, a ‘universal’ tool like this is by far the most efficient mechanism to charge the world a cost of doing business with America (a concept the youth of today will more easily liken to “gas fees” paid in the world of crypto). It has also raises the policy ‘baseline’ to a figure greater than zero, which I discuss below.

This baseline 10% has both more or less been accepted without reciprocation, by every major trading partner including the EU and China, regardless of vehement struggles over additional duties on top. Whether this 10% is the only tariff, like Britain, or whether it is just the minimum, like Japan and Korea who currently have 25%, the standard has been set and moreover will be very likely here to stay – any future US administration may renegotiate on specifics, but will almost certainly leave the baseline in place. It is now quite simply a fact of commercial life.

Secondly, there is China. Amidst all the turmoil (which may be part of a grand plan, but frankly who knows), Trump has continued his decade long trade strategy of increasing tariffs and daring China to fight back and contest who holds the most leverage. This bluff has been called several times, and has resulted in the US turning the net tariff differential (the principal measure of ‘success’ in any tariff strategy) in its favour for the first time in living memory.

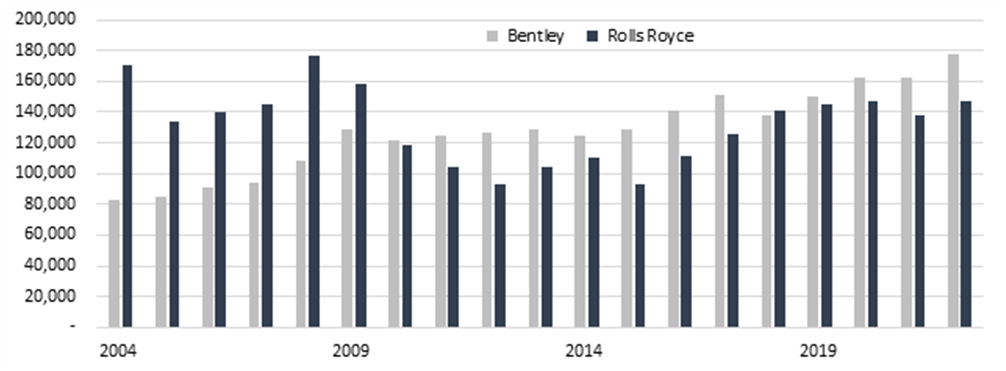

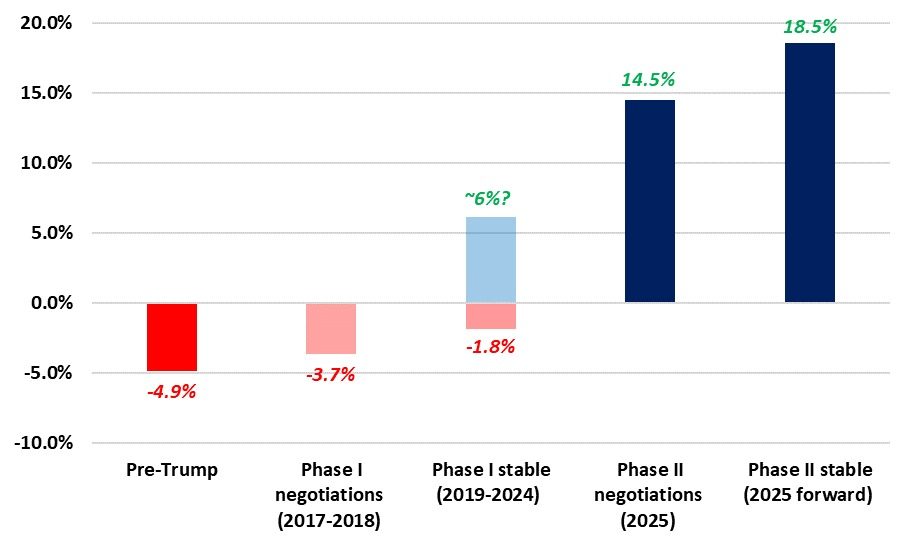

US net tariff differential with China, 2016-2025

Sources: PIIE, underlying sources

Notes: 1. Trade-weighted tariff rates in 2016 were 8.0% on US exports to China vs 3.9% on imports; 2. While the notional differential achieved in Phase I was -1.8%, in reality China unofficially suspended many import duties leading to a positive differential under Trump’s first administration; 3. 2025 forward numbers based on latest round of negotiations ending May 2025.

When Trump first emerged on the scene, the institutional trade nexus between the US and China, comprising both WTO and bilateral arrangements, was such that China imposed about 5% more duty on the US than vice versa. Liberal economists contended rather tritely that this was a price worth paying. Yet over the course of both the 2016-2020 presidency and now in his second term, this negative differential was first reduced and now into a major surplus. China, despite raising tariffs of its own, has acquiesced to the new normal that it must pay the US more than the US pays it, for trade. If anything can be considered a ‘win’, this is what it looks like.

In the meantime, we have seen no sign of the supposed economic slowdown as a consequence of the “trade wars” [sic]; there have been plenty of anecdotal examples of exporters eating the additional cost into their bottom lines; and after the initial volatility, the markets have settled down into a rally. Personally, I regard none of these as important for long term strategic reorientation, but among the breathless commentariat fainting at news from the bond markets, it seems to matter.

And what is the point of all this, might you ask? For me, on the subject of tariffs themselves, this policy has been a triumph of common sense. I have argued for years that the US and others needed to ramp up tariffs for several reasons.

One main consideration is that today’s global economy is no longer that of Ricardo’s. The applicability to free trade theory to a landscape of non-tariff barriers, unfungible services, and complexities of cross-border supply chains are extremely limited. Furthermore Ricardo assumed (as all economists tend to) agnostic counterparties motivated and constrained by economic incentives including public wealth and living standards; he did not factor in malevolent strategic actors who would happily pay a cost to bend a supposedly neutral system to their own agenda. Let us be in no doubt: if Ricardo were alive today, he would be pushing for trade tariffs.

Another outcome is the pushing back on the idiot savancy© which has led the technocratic classes to glorify “zero” targets – tariffs, interest rates, inflation, exchange volatility, even carbon emissions (though strangely not taxes or immigration). In most areas of public policy, however, zero is convenient for bureaucracy but wrong for the public. Low rates can occasionally be enjoyed as an output, not an input, but freedom to raise them are the safety valves required for cyclical management of the economy – sometimes you want inflation; sometimes you need currency devaluation. Tariffs, too, are a tool whose starting point (the ‘baseline’) needs room for manoeuvre both up and down – as a decade of near-zero interest rates have demonstrated, autistic ambitions hamstring policy tools needed to meet new challenges (I will write separately about this whole topic). So 10% or so suits the US quite nicely.

How tariffs will end up functioning is an unknown, due in part to how long OECD governments have allowed their muscles to atrophy in recent decades. And nothing scares technocrats more than the unknown. Yet beyond the anecdotal evidence of implementation, we also now know that the first round of Trump’s changes in 2018 led to substantial fiscal outcomes, with customs revenue doubling from US$35bn per year to US$70bn and well beyond.

This income is forecast to continue rising unless the economy tanks, but little sign of this. How the US government chooses to use this windfall is a separate matter, but the income certainly exists and one reason Biden chose to continue Trump’s tariff policy was that nobody wanted to look this gift horse in the mouth. While revenue raised is not central to the justification for tariffs, they offer an important lesson in how erroneous predictions on effects can be.

Most importantly of all, regardless of whether one supports increased trade protectionism or not (and I accept there are plenty of arguments to be had on either side), Trump continues to challenge the orthodoxy that such sharp directional changes are not even possible. Because for every protagonist arguing against the economics of tariffs, several more are usually hiding behind the sophistry that “he will never be able to do it, anyway”. These are the people cheering on the bond market turmoil or China’s retaliatory duties, unwilling to admit out loud that if it could be done, it might actually make sense for people, even at the cost of being vastly more inconvenient for the beneficiaries of globalisation.

As with defence or immigration, Trump has shown that none of these shibboleths are untouchable. The governing classes, while self-interested in keeping the policies of the last fifty years in place, has been surprisingly ineffective at stopping Trump from turning 180 degrees on tariffs or NATO or Iran, despite loudly arguing that it could “never be achieved”. So it turns out that the system, for better or worse, can be changed. Perhaps after all it is actually Trump who is living Obama’s best life, as he surveys the world around him and tells voters “yes, we can”.