Most think they have been strategic, when in reality they have just been gambling

My LinkedIn has been showing the first signs of waking up, in recent months, to roles centred around ‘strategy’. This broad term takes into account a range of positions, all of which are yet nebulous, but which nonetheless are being formulated by leadership. This reflects the changing nature of corporate life in the Asia region, where companies are struggling to grow the way they want – but most have not yet worked out why.

To quote one friend of mine, with a background in family offices, “a lot of Asian fortunes are going to be lost in the next decade or two” – principally (though not solely) due to declining asset prices in real estate. Urgency and heroism at these family groups are what is needed, but either these characteristics are not present in the generation governing them, or that energy does not have a constructive home.

The true scale of slowdown in the region has not yet been recognised. Corporate owners generally are too illiterate to distinguish between real and nominal GDP growth (an issue I have written plenty about before); comfortable board rooms in Hong Kong, Singapore or London survey Asia as a market which has slowed – but just a little. After all, real GDP in China dropped from some 10% on average in the first decade of the millennium, to some 7% in the second until 2019 (it has since spooked markets by generating only 5% over the Covid years). SE Asia was never quite that high, with GDP averaging around 5% in both decades. All pretty healthy.

But corporate top lines and bottom-lines are not real, they are nominal. And importantly, nominal GDP fell precipitously over the same period, almost halving in local currency terms from over 18% to 10% over the two decades (in USD term, growth rates have been even lower).

In other words, the age of Asian growth is over. We are well past the phase of the rising tide – not just in China, but more or less across the region. This impacts both corporate performance, as well as property prices. Asian groups have, on the whole, seen their returns stagnate over the last decade compared to the decade before; and importantly they have fallen in line with nominal GDP growth – in other words they are ‘maxing out’ their ability to squeeze more. They have been able to outstrip GDP here and there, but it started running out of wiggle room well before the change in interest rates which seems likely to be with us for some time. Now, the future of growth looks even bleaker.

So where does this leave us? The reality is that most corporates in Asia have not really had a ‘strategy’ per se, even if they claimed to have. Instead, they made bets in a benign environment, where they really did not have to be very clever to make money. Most sectors across the board grew decently in a +18% CAGR world. Furthermore, a majority of these family groups already owned assets – principally prime real estate – which rewarded rent-seeking and minimised the need for innovation. Where such groups did venture into the unknown (Adrian Cheng in Hong Kong being perhaps the most prominent), things did not go so well. These businesses do not just need a new strategy, they need a strategy in the first place.

So what is ‘strategy’? Well first, it is easier to understand what strategy for such groups is not, particularly some frequent misperceptions and conflations.

- Strategy is not tactics (destination is needed before details)

- Strategy is not budgets (even though finance is how control is maintained)

- Strategy is not transactions (deals come only after we know direction)

Strategy is about what you want to be as an entity, and the broad direction of how to get there. In Asia, the biggest omission from corporate owners (who tend to be family) is not focusing enough on coherence and identity. Conglomerates are perfectly acceptable in their way; we have, since the rise of the tech giants on either side of the Pacific, witnessed a renewed era of conglomeration in the form of Google, Amazon, Tencent and Alibaba. Single sector focus is not important or the only key to generating shareholder value. Rather, bringing together wildly different businesses can be successful where the overall narrative of who you are still holds. You do not need to have operational synergies in order to have an ownership cohesion of even a sprawling empire.

‘Strategy’ is also about power. The preeminent objective for family groups in Asia, with minorities playing a lesser role, is preservation and the ability to keep your destiny in your own hands. Near-term returns are important; dividends are crucial; but above all else, is it control which is paramount. Life is a constant battle for control – against the government, against competitors, against suppliers, against customers. Strategic thinking is designed to look beyond the financials to the power dynamics in the market – for instance owning the loss-making delivery business which allows control of consumption for your upstream FMCG, or owning the low margin bank that finances speculative capital in new industries.

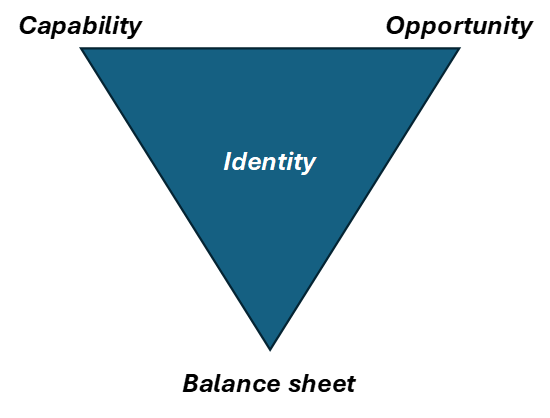

The purpose of ‘strategy’ is therefore to solve the triangle of dynamic forces which determine how a group can move forward. Capabilities either exist or need to be cultivated or acquired; opportunities need to be identified, sourced and validated; and the ability to invest, either through equity or debt or partnerships, has to be planned.

The tricky part is that moving each of these impacts the other two, and ‘strategy’ is therefore about determining how best to balance them to reach the overall aim and keep your identity. Buying new capability through M&A, say, might expand your opportunity set, but weigh on your balance sheet. Restricting your gearing risks not just limiting your opportunities to invest, but also stretch your existing resources in management.

But central to all of this – and where Asian family businesses are particularly lacking – is the need to build or maintain a true identity about who you are and where you are doing. In this region in particular, business owners undervalue how much identity is needed as a pay-off for lack of financial incentivisation and a demand for loyalty (same in politics). Hence identity sits and the very heart of how to think about ‘strategy’, a sine qua non from which all other plans flow. You need a cadre of people who remain loyal to the cause and hence work to protect a family’s interests across generations. They need, more or less, to feel like they are part of a partnership in the traditional sense; mercenary superstar management is the death-knell of the family conglomerate.

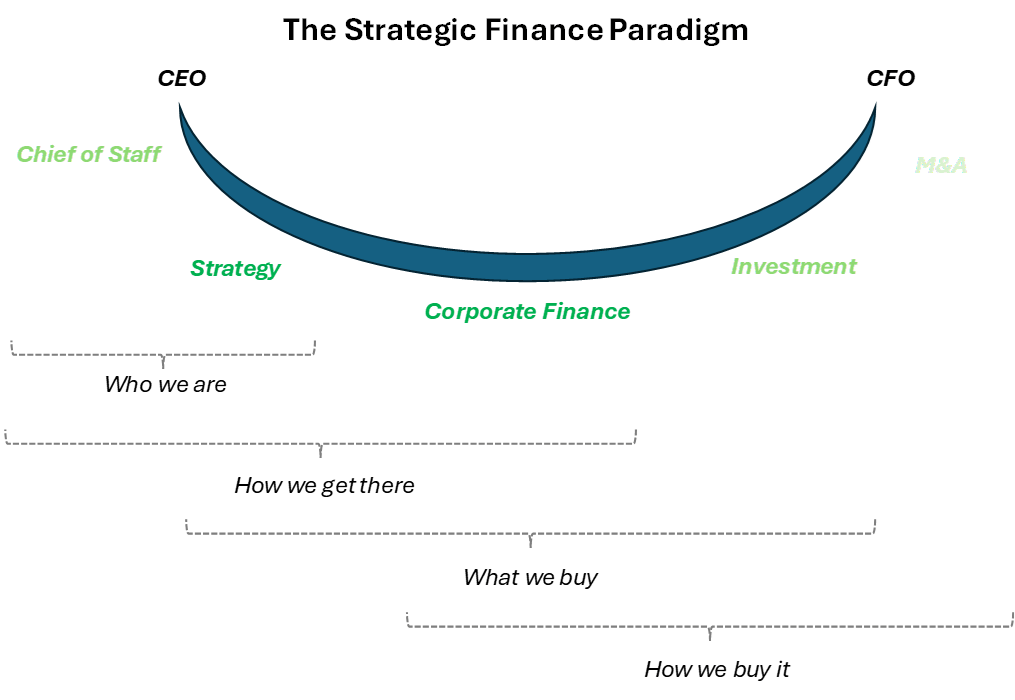

Which brings us to organisation. Lots of people think that they “do” strategy; yet more others have such a title; a third group really need to be strategic. The problem is, the three rarely converge. People confuse strategy with tactics, ‘strategy’ titles often mean doing M&A, and leadership is often bogged down trying to manage stakeholders and incremental decisions to really think strategically. Divisions and subsidiaries cannot be left alone to decide their own fates; their management is rightly limited to seeing things through the prism of their own industry. They cannot offer holistic views about the portfolio and they are not positioned to leverage the strengths of a group overall.

Yet ‘strategy’ is too much for just the Chairman or CEO to undertake, and still less the CFO – although financial control remains key. Getting ownership to think about identity and vision is a skill, and it needs focus. It needs one or more thoroughly invested people at or near the top to shape it and keep the flame alive. As discussed above, there are a range of titles or roles that reach across the spectrum of what I call “strategic finance” – both vision and execution.

And ‘strategy’ will only get more important. Some family groups still live under the auspices of an all-dominant chairman; others want to believe that they should interfere less in their businesses. But one thing binds them both: they underestimate the necessity of a wider, more bought-in middle who understand both the family and the firm, and who are invested in the strategic long-term wellbeing of both. Doing better is not about doing less or doing more, it is about understanding what is strategic and what is not – whether in capital allocation, M&A, organisational structure, portfolio evolution, employment programmes, partnerships or even investor relations.

The urgency and heroism mentioned at the beginning is what Asian family groups will need to survive. They may get lucky with the scion which comes to power, but with or without that, they will need to embrace all those things they found too intellectual, too esoteric, too academic; they will have to start doing ‘strategy’.

Notes:

- For GDP growth, data set is in GDP current LCU

- “Emerging Asia” comprises China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia

- “Total Asia” comprises above plus Japan and Korea

- “Asian conglomerates” comprises Jardine Matheson, Astra International, CP ALL, Keppel, YTL, First Pacific, Uni-President, Sime Darby, Swire Pacific, ThaiBev, SM, CITIC, Ayala and JG Summit

- “Asian property groups” comprises Hongkong Land, Sun Hung Kai, Swire Properties, Henderson, New World, CK ASSET and Wharf REIC

- “Japanese trading houses” comprises Marubeni, Itochu, Mitsui, Mitsubishi and Toyota Tsusho