China’s rise is not about following the conventional economic norms, and the reality is that an ageing population is probably better than a young one

China has always been a black box. For the whole of my professional life, companies (investment banks being amongst the worst) happily hire someone – anyone at all – who claims to know the Chinese market if they can make even a sliver of money. Consequently, these people are given free rein to build their own silos. For boards in London or New York, China remains “a faraway nation of whom we know nothing”. It is from this mysterious, exotic ignorance that reliably insightful commentators, from publications which should know better, produce some tired answers to tired questions. Sad to say, amongst them was a recent piece from Martin Wolf at the Financial Times titled The Future May Not Belong to China.

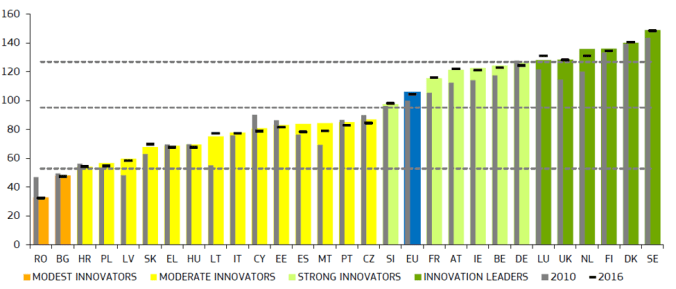

Now, the future may very well not belong to China. Much of what Wolf outlines from his Capital Economics report (rather too much from one source for my liking) is unarguably true: the over-investment, the under-consumption, the increasing corporate debt and reliance on exports. But they only change from fact to “problem” when seen through the same old prism of economic development. China though has been disrupting the whole framework through which one sees these issues, confounding a whole mini-industry of untiring China bears. Who can forget the inflation crisis of 2010 – 2011? The Chibor crisis in the summer of 2013? The stock market crisis in 2015? The capital outflow crisis over 2016 – 2017? In each of these and many others besides, China was to be “found out”; it never was, not because the facts were inaccurate but because the basis for observation by outsiders was so incomplete (although to be fair some of the facts were also inaccurate). The fact that the naysayers and doom-mongers have been consistently wrong may be a cheap point to make, but it is worth making nonetheless. The only laws of economics, it seems, are the ones amateur journalists derive from their undergraduate readings of Adam Smith, Ricardo and Keynes.

A non-exhaustive list of China bear headlines since 1990

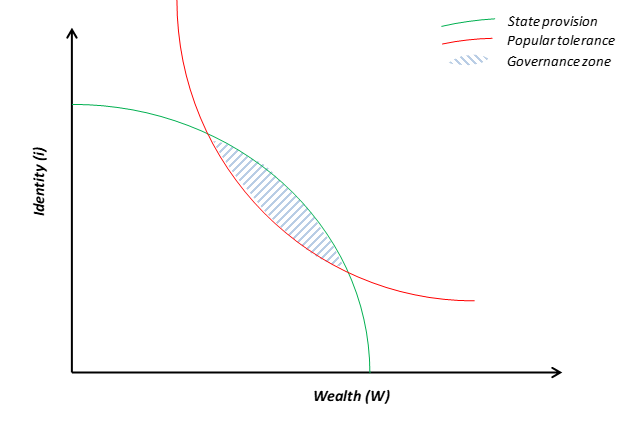

However I would submit two additional unrelated and possibly more controversial theses. The first is that the way China encounters these perceived crises is actually a mark of its success in terms of being on a pathway to global power, rather than a failure. There is a reason why China encounters “difficulties” where Japan, during its own precipitous rise in the 1970s, did not: China is actively trying to change the world it is living in. These crises are the tremors generated by moving tectonic plates, as Chinese objectives grate against the rules and outcomes it is being measured against. Currency and capital flows, interest rates, debt and the banking system – these are all examples of Chinese policy that do not make macro-economic sense until you factor in that it wants to change the system and if it plays its cards right, it probably can. We are faced with the first occasion since the United States back in the 1840s, where the world may have to accommodate a new power, and accordingly the rules will change. For China, this friction is good.

Source: The Economist (2010)

To run through just one example of this, let us look at capital outflows. The reason capital outflows seem like a “crisis” is that the Chinese government wants to control the currency rather than let it be determined by the market. To pay for this, it must use foreign exchange reserves to keep the exchange rate stable. This becomes a huge cost when the environment is weak – except that the reason China does this is to try and make the RMB a regionally accepted trade and reserve currency. This could be done through just trade alone, but in China’s case it will also be done through the crypto-imperialism of the Belt & Road and other initiatives. If it succeeds, it will both eat into America’s ability to project power through the dollar, as well as ultimately encourage greater consumption of Chinese-made goods which in turn once again brings capital flows back into balance. It is a risky and expensive, all-or-nothing gamble; but unlike merely acquiescing into the current world system, if it succeeds it will have changed the regional financial and trade landscape. A price, some would say, worth paying.

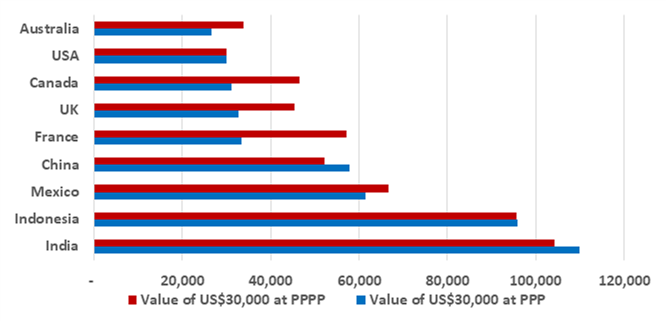

The second thesis focuses on the cliché that China may be facing the middle income trap – that it may “get old before it gets rich”. This is typically paired with the curiously British trait of enthusiasm for India as an alternative story. Yet I would argue that with the coming of automation, China is actually on the right side of history on this and that far from fearing age, the adage should be turned on its head: for many comparable countries it is youth, not age, which will be a great peril; and these countries may be too young to ever get rich.

We have for some decades been fed the neoliberal trope that a younger population is good for the economy, and that pursuit of youth, through birthrates or immigration, is a Good Thing. Yet we are fast approaching the point where this notion is being exposed, because automation is actually a process which will eat into youth employment rather than any other. China’s workforce is actually declining and has been for some years, just in time for robots to start taking over.

The process of classic industralisation is just one of various models for a country to develop. But in this particular model, families can contribute labour rather than capital in order to obtain greater earnings, and thereby over time accumulate household assets. For many countries though, this industrialisation may never now be possible. The Economist noted as much when opining that the pathway of development exhibited by the China + ASEAN axis is probably irreplicable by anyone else including markets in Africa and South America. Goods may be manufactured in some of these economies, but it will be robots that do most of it and young median households will never cross either the asset-owning or educational thresholds required to survive automation before it hits.

Now, it may be that these countries find other models to become rich, but I doubt it. Agriculture or resource extraction will be possible for only a precious few. The mercantile model is not stable or sustainable. Services, as we have seen, actually produce a lower return on labour than industrialization does since jobs are often of a lower quality. In any case one of the stark lessons of 2016 was the fact that in 29 out of 50 states in the US, trucking was the single most common form of employment – and this, more so than manufacturing, is where automation will first hit.

Source: NPR (2015)

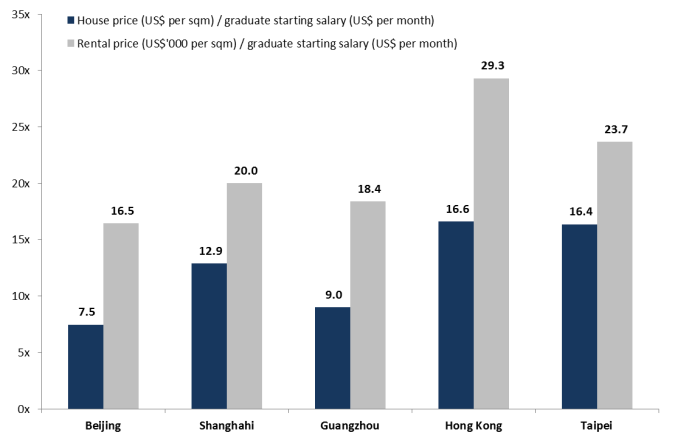

The fact is that to weather automation, median family assets need to reach a critical mass enough to be “invested” into the economy such that they can be gainers from robot productivity rather than victims. The most obvious if questionable form of asset-ownership would be home-ownership, but in an ideal world it would take other forms. China’s urban population has just about caught this train (financial income growth has far outstripped wage growth in recent years), but younger populations in India or Vietnam may not make it. Young people inevitable have fewer assets having had less time to earn; if their family does not reach this critical automation-neutralising financial position, they face eternal unemployment. OECD economies mitigate this conundrum somewhat through welfare transfers, but welfare is another privilege of long term asset accumulation by Society – a privilege emerging markets do not have. It is a race against time and any country that fails to achieve this will be left without a chair when the music stops.

In this context, I have little time for those who argue, as Wolf does, that India is “the most interesting other economy” (Americans I have noticed, tend to use Vietnam as their preferred example). As one of my friends commented, “the human race will probably be extinct before India has an airport like Pudong”. Taken individually, each of these points (China’s extra-economic rise and youth being a greater concern than age) have huge implications about the rules and framework for emerging market development theory. Taken together however, they may represent a perfect storm which leading to an inflection point in global economic development. In this case, being wedded to the old ideas, commentators like Wolf are probably missing it.