On election night, I – unlike some around me (they know who they are) – was not losing my head. I had reasonable confidence of a substantial Tory majority, and had even put my money where my mouth was – being a buyer of a Tory majority at 44 in the spread betting markets. I had one central thesis: that the British electorate does not produce hung parliaments when there is a clear choice before them. Rather, hung parliaments only occur when the parties cannot distinguish themselves from one another (1974, 2010), or when they are unknown quantities (2017, pre-war). By this logic, Boris was in a good position to win outright.

This was despite the best attempts by the media to misread the polls. Like sub-par generals, journalists are always doomed to fight the last war, and the pollster who did “best” last time always exercises a disproportionate influence on their discourse the next time around. This year it was the YouGov MRP’s turn for lazy writers to place too much faith in, never remembering that no one pollster has ever been the “most accurate” twice in a row. In the event, the polls-of-polls were all broadly correct.

Of course there are other points of note about the Tory performance. On the one hand, there can surely be no denying Theresa May her contribution to breaking the Red Wall, and perhaps it really needed two heaves to get there; on the other hand, the media narrative on Boris being unpopular was I think well wide of the mark. Amongst key voter demographics, Boris was a positive, not a negative, and not just in contrast to Corbyn. Anyone who witnessed the acceptance speech by Ian Levy, the winning candidate in Blyth Valley, or to the reactions in Workington or Darlington, cannot doubt how central Boris was and how well he played on the doorstep as a loveable scamp who transcended class in his determination for Brexit.

Yet hidden amongst all the shock and turmoil lies a more profound truth: the Tories have been quietly improving their standing amongst the electorate for the last twenty years. Indeed the party have improved on their share of the vote at every election since 1997. They have also improved on their absolute numbers of votes since 2001 (the one surprise here being the considerable popularity of John Major even in 1997).

Conservative Party vote share and vote totals since 1997

This has not always translated into increased numbers of seats, due to the vagaries of the electoral system. 2017 saw Theresa May lose seats even as she surged to the highest vote share since Thatcher’s first election in 1979. William Hague, too, managed only a single net gain in 2001 despite a whole percentage point increase in votes. But set against this is the extraordinary fact that the party have now managed twice, in three elections, to work its way out of a hung parliament and back into a majority – a particularly difficult feat.

The cherry on the cake, of course, is that for those of us who lived through the dark days of the 1990s, we live to see a Tory government now likely to rule for at least fourteen years, and maybe nineteen. And whereas every other administration has won their biggest victories at or near the beginning (1945, 1966, 1983, 1997) only to see a long slow decline, somehow we have endeavoured to our greatest moment so far at the fourth time of asking, after a decade of being in power and all the scrutiny that comes with it. This is unprecedented and we are I think, allowed just a moment of self-satisfaction.

Majorities won by successive single party governments since 1945

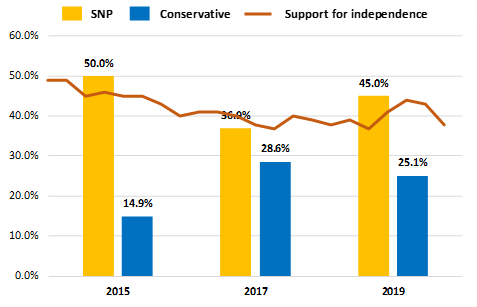

The one dark cloud being touted is Scotland. It will prove impossible for Boris not to yield to the SNP for a second referendum, they say. Yet for my own part, I reject this media interpretation. We should be clear that the SNP, whilst doing well in absolute terms, underperformed their own expectations and their previous results, and ended the night a slightly disappointed party. At 45%, their vote share was notably lower than the milestone 50% that they achieved in 2015, at the height of their post-referendum popularity. In seats, too, they failed to obtain the psychologically important 50 seats which they had set for themselves, and which would have cost Ruth Davidson a chilly outing in Loch Ness.

SNP and Conservative Party vote shares since 2015 vs support for Scottish independence

Source: Scottish independence polling from YouGov / The Times

Reading overlying themes onto partisan performances has its limitations. Reading Brexit results onto Tory or Labour support is impractical, for instance. But this is less so for one-issue parties such as the SNP or the Brexit Party. Their secular decline in their vote share since 2015 reflects the commensurate decline in popularity of the Scottish independence proposition over the same period. Much as the SNP have made headlines with the help of simplistic reporting, they are actually worse off than they have been in the recent past.

And here, given the success of my previous theory, is my second one: the popularity of independence in Scotland correlates directly with the efficacy of government in Westminster – not the nature of that government or its political colours, just plain ability to govern. Hence why the build up to 2014, with a coalition in place, led to one peak; the minority of 2017-2019 another (as were the mid-to-late 1990s). But I predict that as Boris gets his feet under the table and gets on with life, Brexit included, Scottish sentiment will begin to recede. Boris need not pay such calls for independence any heed, and all credit to him, he seems to be headed this way.

Support for Scottish independence (1978 – 2012)

The progress that the Conservative Party has made since the mid-1990s is a tribute to various leaders, each in their way: William Hague for his “night shift”; Michael Howard, the man who arguably saved the Conservative Party with his performance in 2005; David Cameron and his decontamination; May and the recognition of the new tectonic plates of class and economics; and finally Boris, who with his ambiguity over Brexit somehow captured the skeptical but generous spirit of the age. Even Iain Duncan Smith was a useful placeholder. The fact is that this 80 seat majority is a tribute not just to Boris’ political skills, but rather to a long, slow, and painful rebuild which for all its highs and lows, has seen indomitable progress towards power. Just what the Conservative Party has always been about.

************************************************************************

A slightly self-congratulatory update (2 Jan 2020)

First, it seems this theme of long term progress has been picked up by various commentators, such as Martin Kettle at the Guardian, who notes that:

“The Tories have now formed four governments in a row. Remarkably, they have increased their share of the vote for the last six elections. They have 200 more MPs today than in 1997. Those who sit for seats in the north and Midlands have got most of the attention, and rightly so. But the tightening Tory grip in parts of the south that were once marginal also matters. The Tory advance across Wales is dramatic. And they remain a player in Scotland, something Labour can barely claim. They are UK-wide again. And they now have a new generation of MPs who can shape their party.“

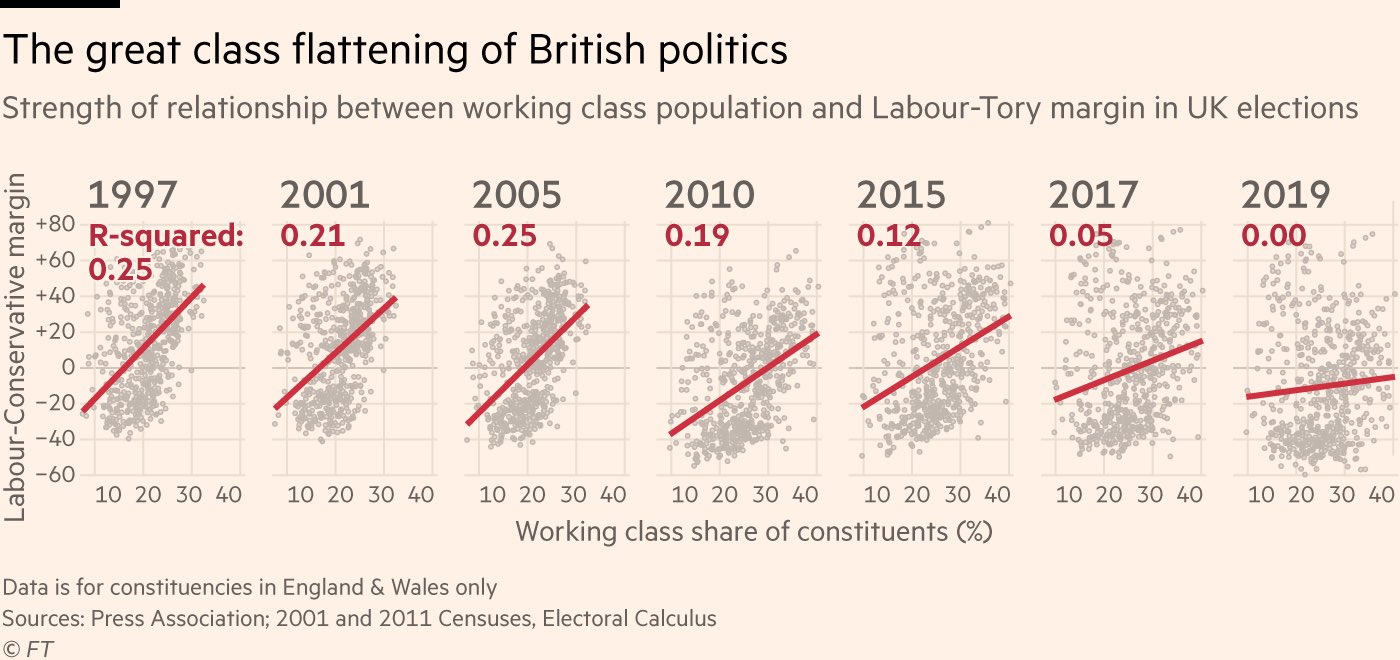

Secondly, there was an interesting graphic from the Financial Times talking about the Tories and the working class:

However whilst the FT was trying to make the point about Tory inroads, much of this graphic simply demonstrates the underlying improvement in performance, which would naturally eat into traditional Labour voters since Conservative success basically equates to Labour decline. Either way, the choice of 1997 as the starting point is notable and the story a component of what I outlined above in the original post.