Plouffe’s inability to recognise why issues like trans rights swayed votes is the reason why he is bringing the outdated Obama era down with a crash

Having kept his head down (with some justification), David Plouffe recently emerged for the first time since the election to contribute to some of the very worst takes about the 2024 election, on Pod Save America.

It’s very easy these days to understand who has experienced an ad, so we were feeding a lot of digital ads to people who might have saw that spot. But at the end of the day, we were spending a lot of time with voters in these battleground states both quantitatively and quantitatively, and this trans ad was not driving vote.”

To say that Plouffe is from a different era is an understatement – he is now the Paul Krugman of electoral politics belonging to a barely recognisable age. In his defence of the failed Harris campaign, however, we can identify a mental anachronism which will continue to drag the Democrats down, even after being shocked by the force of nature that is Trump in three consecutive presidential elections. As a supporter, historically, of Bill Clinton, Gore, Kerry and even Hillary in her 2008 incarnation (not so much eight years later) this pains me. Everyone is offering their views on how “out of touch” the Democrats have become, so here I offer my own.

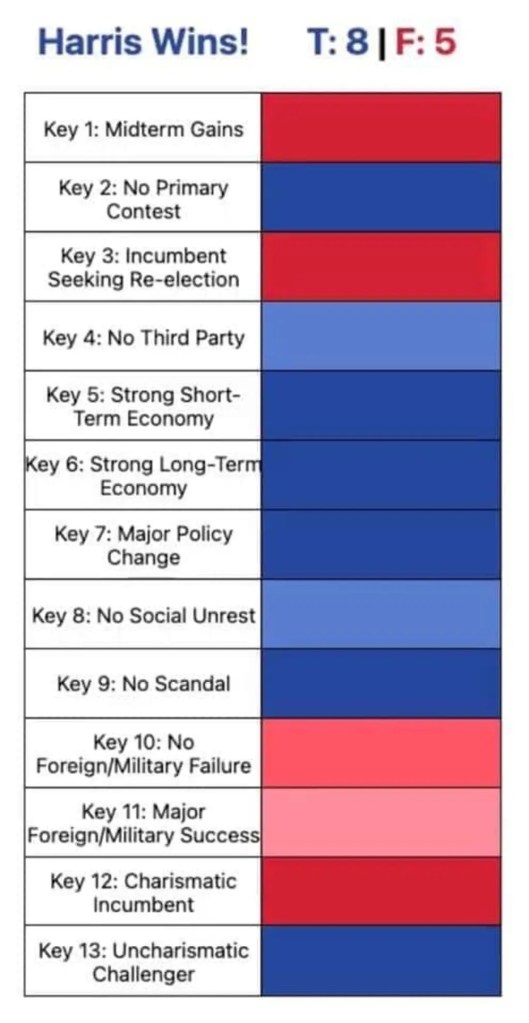

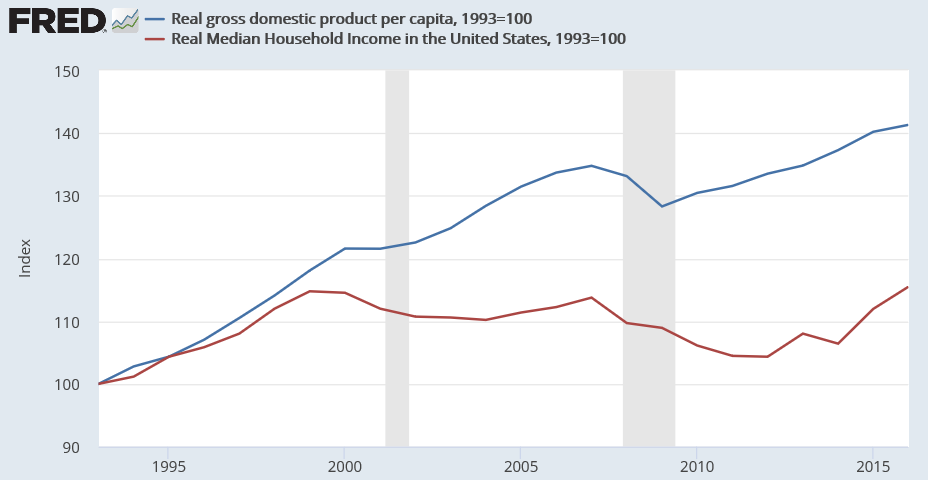

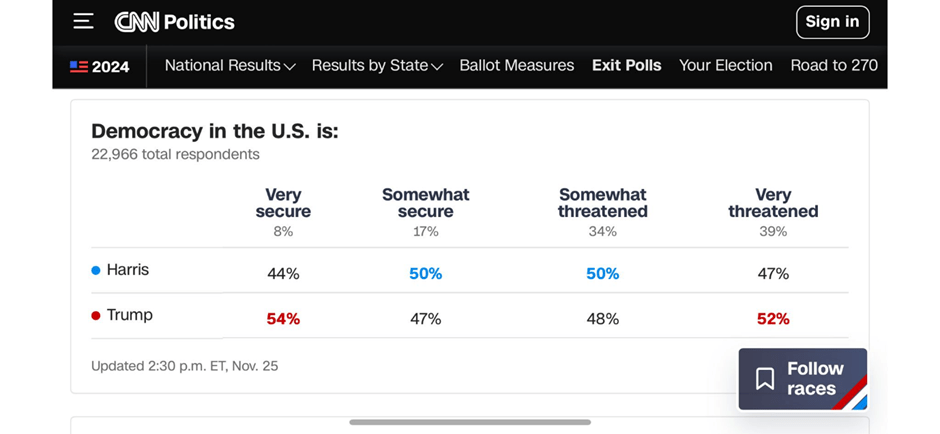

First, the Democrats appeared to make a basic error in interpreting polling on voter priority as monolithic support for their side. The most obvious case was seeing “the state of democracy” as the biggest concern for voters, but assuming that such people must be anti-Trump side. As the exit polls showed, among those who considered democracy threatened around half actually supported Trump, not Harris:

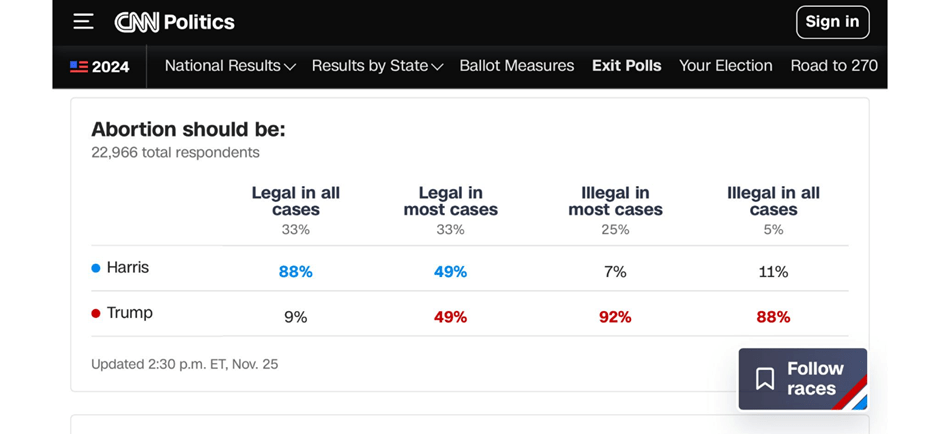

Even if we accept that people voted on the basis of just this one issue, it turns out as many considered the ‘lawfare’ campaign against Trump as a threat to democratic norms as did the events of 6 Jan, and Democrat pursuit of the argument that “Donald Trump is a fascist” were not only failing to gain traction but may actually have been counterproductive. The same applies to abortion, which earlier on in the campaign was considered critical: among the one-third of voters who thought abortion should be “legal in most cases”, voters were split evenly between the two candidates:

If strategists such as Plouffe were not even bothering to dig into the numbers behind the headlines to this basic level, it is hardly surprising that they were wasting their resources based on biased assumptions and projection.

Secondly and more importantly however, is the very use of voter prioritisation polling. Most examples of such polling were single answer (rather than, for instance, allowing respondents to choose as many as were important). This created two problems: the error of forced choice and the error of colouring. Forced choices make people go with obvious and pronounced options even when other issues might cumulatively be more important (eg the economy might be outweighed by adding immigration + crime together). Colouring is the consideration that a seemingly insignificant issue by itself still adds a great deal of colour to the candidate or party, influencing voting subtly.

The fact is that most people do not vote on ‘policies’ other than very occasionally when a policy is so simple that it cuts through all the political noise to become totemic. These are so rare that we are hard-pressed to even recall many instances – although Trump’s promises on trade treaties in 2016 comes to mind (as well, perhaps, as his “no tax on tips” policy this year). Elsewhere, the chance to buy your council house under Margaret Thatcher in 1987 is an example from the UK, as was Jeremy Corbyn’s land value tax proposal in 2017. Rather than policies, voters pit a general sense of where policy proposals are headed (eg “lower taxes”, “tough on crime” etc) against a matrix of what a candidate is ‘famous’ for. If the candidate is not well known for the economy for instance, no amount of policy proposals on that subject will mean anything. People vote for their impressions about a candidate, not so much the content.

Which leads to the issue of trans rights, which Plouffe so airily dismissed as “not driving vote”. He was of course correct that it affects tiny numbers of people, and directly animates only a few more; but he is wrong that Harris’ well known past history on trans matters did not colour voters’ impressions of who she was and what she tends to care about. Certainly, she did not come across as tending to care about immigration or inflation, two subjects Trump did convey; on the other hand the trans dsicussion, while not shifting votes directly, added up to an impression of her priorities. On a broader level, it brought into focus her judgement – “is a politician sanctioning free transgender operations for prisoners really worrying about the same things as me?”. Issues can be obscure without being innocuous.

(The same, by the way, was true of Brexit where for years the polling had told us that the issue of “Europe” was not a priority:

Yet this totally missed the point that while in a forced choice, it was not important, at the same time its many facets coloured huge chunks of the public discourse about Britain and the efficacy and power of its government to effect change on matters such as the economy or immigration. Rightly or wrongly, the democratic overhang created by EU membership far overshadowed the importance of the actual issue in voters’ minds and this manifested as a groundswell of discontent which could barely be contained – if Cameron had not asked the question in 2016, a future prime minister would have had to do so within the ensuing years).

None of this nuance emerges in Plouffe’s narrow and mechanical interpretation of voter issues, but it does not take a genius to see how it all connected in the minds of a voter who is only semi-engaged. I will use the parallel of Tinder, where I doubt David Plouffe would have much success, to illustrate the point.

If we strip away the 50% of women and 99% of men who swipe left or right based purely on the photo (although this, too, may be instructive to campaign directors), we are left users of the app having only a quick glance of the few things written down on a profile to decide their choice. Now, imagine a man includes the sentence “vegetarian” in his profile, and consider the consequences. Few women will be so militantly carnivore that they swipe left for this reason alone; but there is no doubting that it somehow adds colour to the profile which will make them think twice. “What does this guy care about?” “What sort of restaurant would we have to go to?”, “Will he force me to only eat lettuce?” and so on. Nobody will admit to vegetarianism having been the deciding factor for their swiping, but you can be sure that it did its job in making that profile underperform in finding matches.

Such structural misunderstandings significantly weakened the strategy Plouffe and his crew were running, well before we get to the litany of “unforced errors” which surely did not help in what was supposed to be a tight race: bear-hugging the Cheneys on campaign; encouraging abortion ballot initiatives in the same election meaning voters could split their ticket and vote for Trump and for abortion; avoiding Joe Rogan and not distancing from Biden; and the ignored sense of scandal surrounding both pretending Biden was mentally capable until June, and then replacing him without a primary. But these need not be litigated here, because the Plouffe team had made historic mistakes in reading voters’ preferences well before the campaign minutiae.

It is, in a sense, rather poetic that the governing classes in both parties (and in the UK) who for so long have sought to reduce politics to a pseudo-science of well-placed dog whistles and esoteric metrics about the economy, should be hoisted on their own petard. Trump offered little if any direct policy solutions to the questions of immigration or inflation, but voters felt he understood it in his marrow. The Democrats need not had offered policy answers either, they simply needed to find a candidate or a message which showed they too understood the problem. But having spent three decades telling voters that life is all about the statistical evidence, about management, about professionalism and about making sure the ‘system’ worked, voters then went on to rightly judge them on these very metrics. Prices were up, groceries less affordable, government seemingly ineffective. If you live by technocracy, you will die by technocracy.