My attention was drawn to this piece, detailing a new book – Unfinished Miracle: Taiwan’s Economy and Society in Transition – which feels like it could be quite important. Whilst I await the final version, I nonetheless would offer a few thoughts on Taiwan, and not least its asymmetric relationship with China.

Few states are as substantially bound to and distorted by a single other large, connected country as Taiwan is by China (for the record, I do not acknowledge Taiwan as a sovereign nation but will for the purposes of this blog post refer to it in the short hand). The only other examples which spring immediately to mind are the relationships between the US and Britain, and between Brazil and Portugal – and both of those are largely historical cases. In each instance, the existence of the larger and younger frontier came to capture the economic imagination of the wealthier, older land – such that in many cases there was a disproportionate focus on these opportunities at the expense of other potentially more profitable ones.

Taiwan’s love-hate relationship with the Mainland along these same lines appears to be the heart of the thesis offered in the new book. In particular, the writers detail the “three-way trade” in which Taiwanese companies operate an export model using Chinese assets rather than domestic Taiwanese ones, creating employment and generating returns in China rather than at “home”:

“One can see from employment figures that Taiwanese enterprises have created far more jobs overseas than in Taiwan. The top 500 companies employ about 2.5 million people abroad (mostly in China) but only 1.5 million people at home. According to estimates, for every 29 people these companies employ in China, they employ one less person in Taiwan.”

Not every point makes sense to me. For instance the authors start off with the matter of SMEs accounting for a declining proportion of direct exports – which may well be true but I will have to wait for the book to see why it is relevant. After all any economy, as it develops and consolidates along the value chain, should see local export champions aggregate value so that a few higher end entities become the point of export, rather than SMEs serving as offshore suppliers to a foreign aggregator.

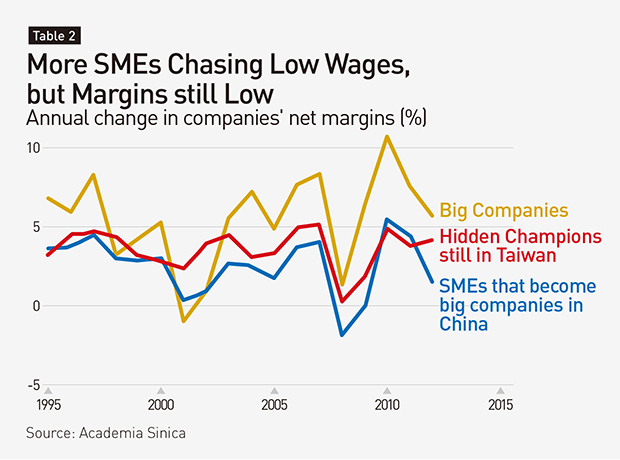

But the issue of how and where Taiwanese companies are making money is of great consequence. If the article is correct, Taiwanese companies are struggling to improve their gross margins despite moving their workforce into the PRC. This is clearly an issue about where they sit on the value chain. But there is another, even more gigantic elephant looming in the room: Taiwan is becoming nothing more than a remittance economy barely differing from the Philippines.

Consider that an estimated two million Taiwanese live abroad – one million in China alone (and half a million just in the Shanghai area). And these are not the old and invalid – they are the young, the brightest, the entrepreneurial two million out of a total workforce of only 11.8m people. Those that can, leave; those that can’t, remain. The social and cultural disjuncture between the diaspora and those staying at home, where graduate salaries are now lower than comparable roles in Shanghai or Beijing, is increasingly stark.

Furthermore, whilst domestic salaries are stagnating, business engaged in the offshore model discussed in this paper (“SMEs that become big companies in China”) are making huge returns, and often repatriating large amounts as a consequence. The earnings made from Chinese exports is leading to a huge asset bubble, particularly in property prices. Those same left-behind graduates are therefore experiencing not only depressed wages, but increasingly unaffordable housing. Even Chinese tourism is driving up the cost of living. The ongoing polarization of Taiwanese politics has its roots in this dichotomy. It is a perfect storm into which the DPP and the Sunflower Movement have emerged, but without any noticeable plan and only trite promises.

Political unrest is an outcome of the country’s inevitable economic model – inevitable because of China’s clever strategy of stymying Taiwanese attempts to trade elsewhere; but giving privileged access to China itself. This integration by stealth has paid huge dividends in terms of making the Taiwanese understand which side their bread is buttered. And it has led to two tangential outcomes – but only one is positive.

First, Taiwan has become a major centre for RMB internationalization. Much of the corporate earnings on the Mainland end up flooding back into Taiwan in its original currency. The island province therefore already constitutes the world’s second largest offshore RMB pool after Hong Kong (which occupies its leadership position for other reasons). Ordinary people are already getting used to RMB banking and wealth products on a day-to-day level, whilst corporates are beginning to issue RMB Formosa bonds. Mainland China is a fact of life for many people, accounting for the relative prima facie ambivalence towards independence.

Secondly and more worryingly, left-behind Taiwan has become increasingly parochial, with a poverty of means being matched by a poverty of ambition. Indeed the Taiwanese even have a term for this, the monstrous concept of 小確幸 which tells them that “good enough is good enough”, the ultimate expression of a “small country” mentality. Fewer and fewer overseas voters – “those that can” – bother to return for elections, especially in midterms, leading to legislative gridlock. And the media, who are left to focus on “those that can’t”, enter a downward spiral of navel-gazing such that news is more akin to a parish newsletter than real journalism.*

All this makes it far more problematic either for the KMT or any “One China” platform to succeed; and easier for peddlers of cheap myths for independence. In this sense, the Chinese strategy of binding Taiwan close may have the unexpected effect of creating a more troublesome rump population who have so little that they also have nothing to lose.

Taiwan’s economic decline is something of a tragedy. Of the four Tigers, its comparative decline is the most visual: Taipei looks like a city that simply stopped developing in c. 1990. Yet for many of us, it is a hugely romantic – and romanticized – version of much that is good about China. Unless someone can come up with a plan of action that captures the essence of all this, the island will continue slipping into a sea of irrelevance, regardless of any formal takeover by the PRC. That will be a situation where everyone is a loser.

* My own speculative thesis is that Taiwan, despite being very educated, has a lower per capita consumption of international quality media such as the Financial Times, the Economist or the Wall Street Journal than other equally non Anglophone societies such as Japan or Korea, or China.