We should look to candidates who prioritise things they can actually do something about

Politics is fundamentally about power, one would think. Liz Truss barely had any when she arrived; now she has gone. Sunak has a little, but not a lot, more. Boris had it in spades in December 2019, but had lost it by earlier this year. Elsewhere I have written about the extent to which Cameron’s 2015 election victory represents something of a modern high, by mandate and power, albeit subsequently wasted.

Yet the politics of the UK these days is largely reminding me of the quote, usually misattributed to Kissinger, that “academic politics is the most vicious and bitter form of politics, because the stakes are so low”, aka Sayre’s Law. The fact is that, like academics eyeing each other warily across the High Table (Maurice Bowra’s adage that he felt “more dined against than dining” was just such an exposition), politicians of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland are now squabbling over an ever-diminishing realm of authority, and this should impact electoral choices.

The Truss-Kwarteng debacle a few weeks ago demonstrates the limitations of what an “independent” medium-sized country actually are. Whilst on the face of it we can deplore financial markets and globalisation, and say to ourselves that this happens even to the greatest powers – Bill Clinton’s healthcare reform in 1994 foundered “fucking bond traders” – we also know that size matters. Taking on the financial markets as a large economy is different to taking one on as a small one. This is a rather Manichean world and Britain is showing itself to have neared the dividing line.

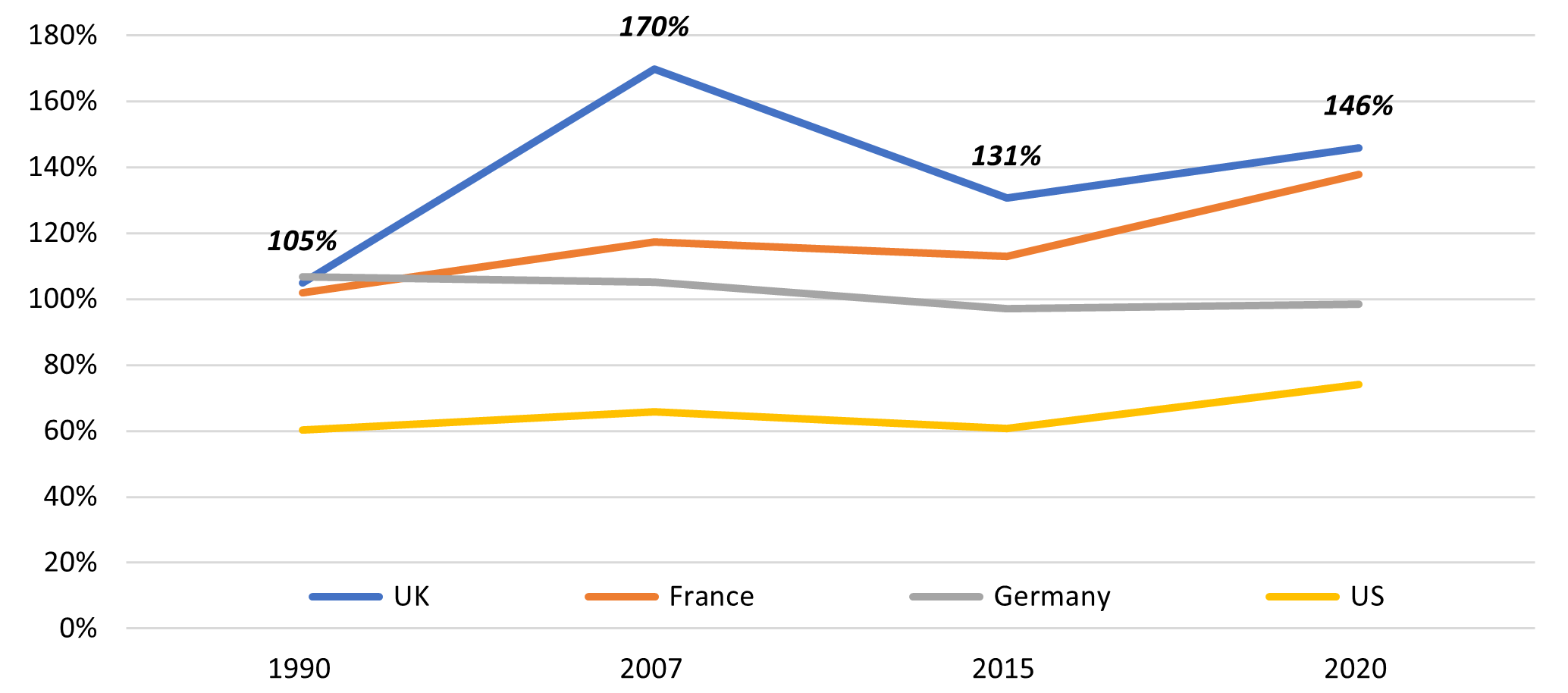

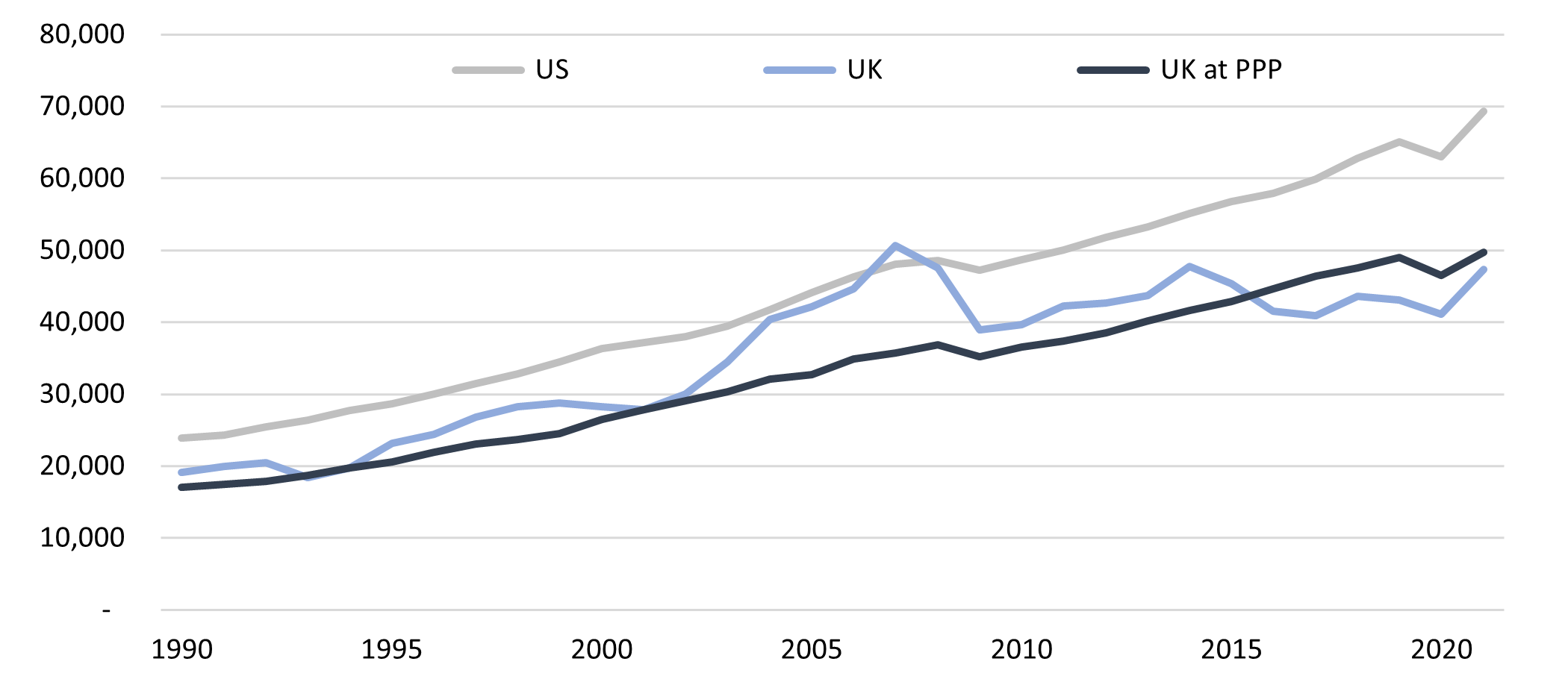

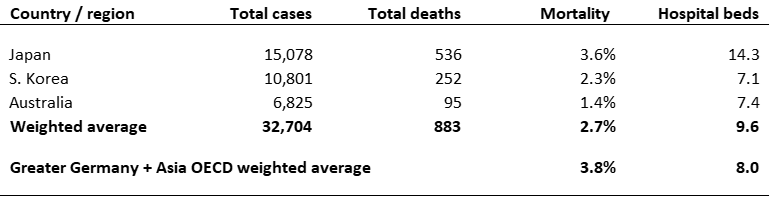

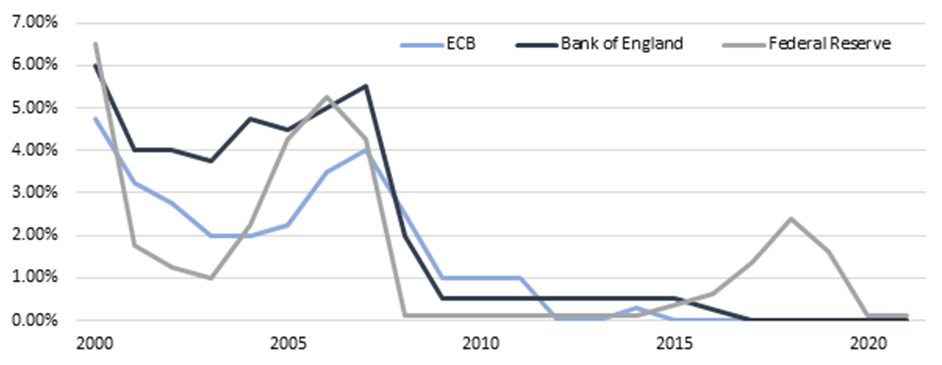

Of course, this could all have been better managed and the specifics of the Truss administration made a bad situation worse. But with Sunak coming in, we can judge whether simply a more articulate and deft touch would make the difference, much as Leopold II succeeded Joseph’s reforms in the 1790s. In fact, he will not, because Sunak understands precisely that Britain can ill-afford to operate outside the bounds of economic convention dictated to us, from the major institutions via the capital markets. Britain cannot have a truly independent monetary or fiscal policy, and Sunak will not want to test this again. This is because of two factors: first, Britain simply is not big enough, with an economic hinterland of adequate heft, to support Sterling and the government borrowing markets on its own. It is almost uniquely globalised in terms of its financing and the shift to this model in recent decades (see my previous note on exchange rates) means that Brexit or not, this will not improve. Secondly, Britain is buffeted about by two economic forces – the EU and the US – who do carry their weight. Interest rates in both will effectively dictate British interest rates; the only scope for freedom are in those occasional periods of divergence between the two:

Interest rates are of course only one lever of economic power (albeit an important one in a financialised economy); but the recent reaction to Kwarteng’s budget shows that fiscal tools are equally to be judged by the narrow minds of financiers of little imagination, and it was not only the exchange rate that collapsed for a time, but also the cost of borrowing which rose (Clinton’s “bond traders” in action). The notions that Britain could just “do its own thing” was always fanciful, at least without accompanying “pain” which no politicians are as yet prepared for.

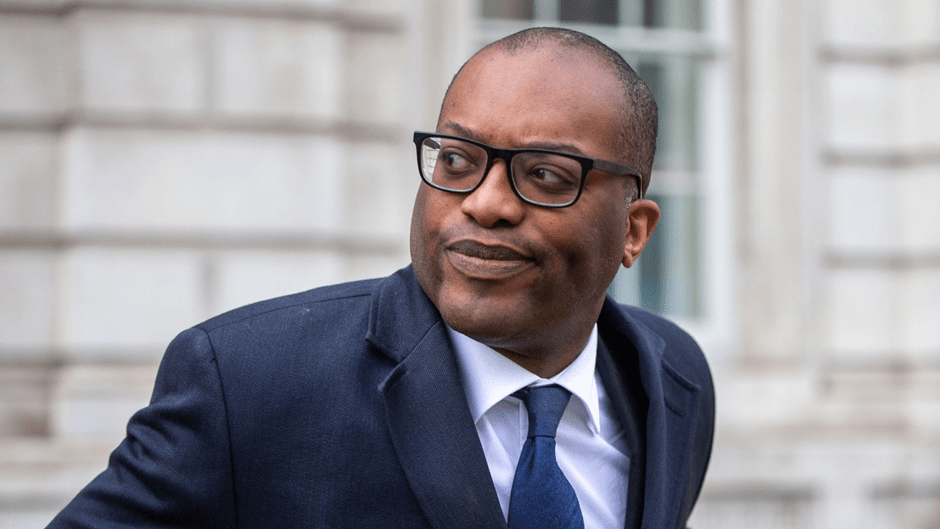

So what does all this mean? Well for me, as an active Conservative Party campaigner and even one-time candidate, it means thinking about leaders who will actually will do something because they are focused on areas which a domestic agenda can still influence. Truss vs Sunak was a false dichotomy because neither promised actionable agendas. I supported Kemi during the last leadership contest, first because I agree with her, and secondly because those areas were one a Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland can actually do something about.

I am more or less talking about kulturkampf in a broad sense. Readers of this blog will know that I prioritise issues of identity above most other things because nation-building is both important and something of a lost art in the globalisation age. Kemi’s most impressive speech for me was her response to the House during Black History Month in 2020, where she laid out some very obvious but important points about British culture:

“Our history is our own; it is not America’s. Too often, those who campaign against racial inequality import wholesale a narrative and assumptions that have nothing to do with this country’s history and have no place on these islands. Our police force is not their police force. Since its establishment by Robert Peel, our police force has operated on the principle of policing by consent. It gives me tremendous pride to live, in 2020, in a nation where the vast majority of our police officers are still unarmed.

On the history of black people in Britain, again, our history of race is not America’s. Most black British people who came to our shores were not brought here in chains, but came voluntarily because of their connections to the UK and in search of a better life. I should know: I am one of them. We have our own joys and sorrows to tell. From the Windrush generation to the Somali diaspora, it is a story that is uniquely ours. If we forget that story and replace it with an imported Americanised narrative of slavery, segregation and Jim Crow, we erase the history of not only black Britain, but of every other community that has contributed to society.”

I commend everyone to watch this.

We can debate the specifics of her message here, but the important point is that she can campaign and do something about this. There is a culture war to be won, through the media, through institutions, through agency capture and other machinations if we really want. These are all within the remit of a leader. What she cannot do anything about, is bring interest rates into the realm of fairness for savers and the hard working rather than constantly inflating domestic household debt. At least, not for now – although if you get the identity question right, at some point down the line you can begin to ask the people for the sacrifice needed to finally rectify the economy and bring it back to something which serves the population and not the other way around.

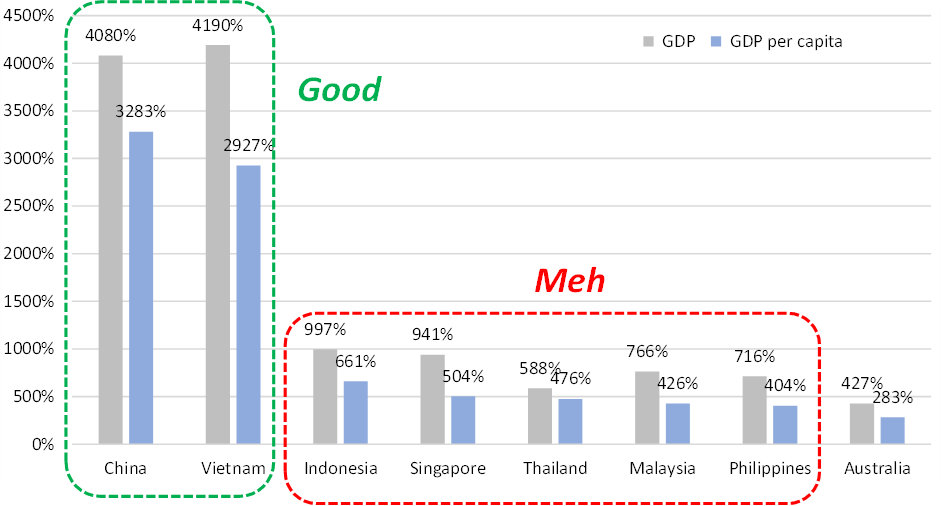

Britain needs to break out of its mindset that it still carries the kind of status and power which allows for true independence. It is this wrongheadedness which led to one specific strand of Brexit support for which I have no sympathy whatsoever – the Dan Hannan school of “Singapore on Thames”. If these politicians spent half as much of their time trying to change things that are changeable, instead of pursuing doctrinaire dreams of economic engineering, Brexit might actually be made to work. In the meantime, the economic shackles we live under continue to demonstrate what a poor economic choice Brexit was. Better panem et circenses.