Just over 25 years ago, an intricate set of corporate activities led to the former Rolls Royce car business, which included Bentley, to be owned by German acquirers. When all shook out, Volkswagen acquired the operations at Crewe and the Bentley brand, while BMW got the rights to create a new concept using the name “Rolls Royce”.

First, we should be clear that Rolls Royce since 2003, successful though it has been, is a ‘phantom’ [sic] marque. Rather like Mercedes’ attempt with Maybach, it has nothing to do with the Rolls Royce of old but rather is the upscale concept that BMW wanted to create to fill a hole in its offering.

Secondly, it is worth noting that in the real economy, rather differently to much of the digital economy of today, real assets and people are worth money. What VW acquired – and wanted – was the factory, the engineers and designers, the back catalogue and experience – of the Rolls Royce entity. That was, rightly, considered to be worth more than just the brand around the Rolls Royce. In dilettante reporting of the time, it appeared to be some major sleight of hand that BMW emerged with the brand name after VW had handed over £430m for the business. But for observers beyond the bankers and bloggers, VW were perceived to have gotten their money’s worth – and more.

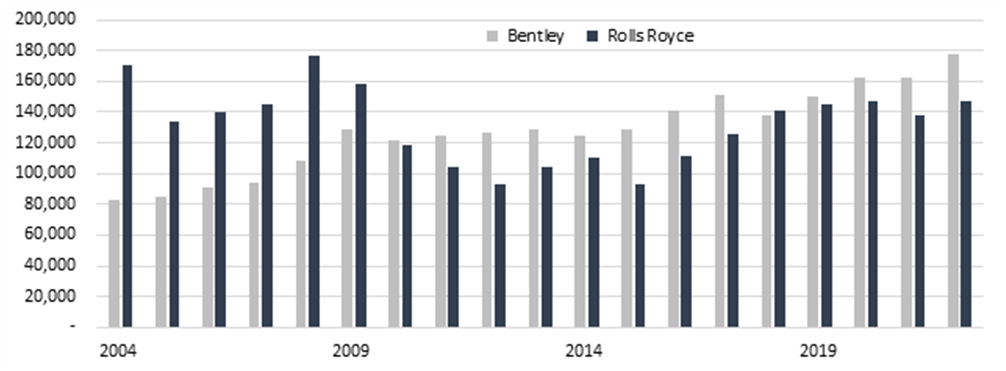

So who has done better since? Well arguably this was a win-win where both carmakers did well with what they took on. While in absolute terms, Bentley has gone on to sell three times the number of vehicles Rolls Royce has (some 200,000 since acquisition, compared to about 65,000 RRs), BMW sell their cars at more than the price of a Bentley.

Total numbers of vehicles sold per year

The boring petrol-head bit

The two brands have pursued rather different strategies given who their owners were. VW, while it already had Audi in the stable (but well before it owned Porsche) wanted Bentley to provide a sporting edge which could be scaled up, rather than owning a ‘limousine’ marque. It therefore pushed the new Continental GT, a model which overnight became a success for London bankers and LA rappers alike. For BMW though, the RR brand was very much about creating a classic luxury saloon (if that can really be used for RR) sitting above their already-premium 7-series.

As mentioned elsewhere, VW went about their strategy by providing the patented W12 engine, a personal project of chairman Ferdinand Piëch, used in their unsuccessful Phaeton luxury saloon adventure, to the team at Crewe. Other than this, and giving the Bentley management a general steer on wanting to see a GT, they left the British business to get on with it – with excellent results. With the arrival of Porsche into the mix a decade later in 2012 though, VW finally started getting serious about the saloon segment, with the launch of the Flying Spur and the Mulsanne. Later again it was coming of the Bentayga, the implausible and slightly absurd Bentley SUV, which has sustained sales in recent years.

BMW went a different direction since they were starting with a clean slate. Working outside of the business over the first five years until 2003, designer and Munich-lifer Marek Djordjevic came up with the Phantom model that would kick-start German ownership of the brand. Sales were boosted again with the launch of the Ghost in 2010, the more affordable line of saloons, but in recent years it is the even more implausible and even more absurd Rolls Royce SUV, the Cullinan, which has been the catalyst – comprising more than 50% of sales since its launch and reaching almost 60% in some years. While Bentley has also had success with the SUV, it has never formed as large a part of its portfolio.

In other words, since 2003 Bentley has really lived off the Continental GT offering, reflecting its racing heritage, while Rolls Royce remained a limousine maker who have evolved into SUVs.

The important bit

Rolls Royce, anecdotally, has always been able to price a like-for-like car at a 30%-50% premium to Bentley since they were each taken over. A Wraith costs more than a Continental GT for instance, and the Ghost costs more than a Flying Spur. However taken as a whole, since introducing the Ghost in 2010 BMW has ended up with a portfolio of cheaper price points on average than VW, as total revenue per vehicle shows:

How this has translated into hard profits for their owners is more complicated. The fact is that neither of these businesses have delivered huge amounts of outright profit. Bentley managed to record a bottom line of £684m in 2022, a record, but since 2003 has dipped in and out of profitability overall. RR has managed to record a small and consistent profit over the same period, culminating in a £97m bottom line in 2022. On an adjusted, pre-R&D basis, Bentley has recorded a 21% profit margin over the last decade, compared with 8% for Rolls Royce. In the context of VW’s and BMW’s overall earnings of €15.8bn and €18.6bn respectively, these are drops in the ocean. Bentley accounts for 4.4% of VW’s earnings; RR just 0.5% of BMW’s.

Moreover, the Rolls Royce profit is overstated since BMW does not push R&D costs into the Goodwood accounts. In fact, it is likely still not profitable after two decades of operation. Bentley, due to its Crewe location being self-sufficient, has spent on average £322m on R&D per year over the last decade, leading to several years in the red. One can assume either that Rolls Royce really is just using BMW 7-series intellectual property, or it is spending similar amounts which would imply substantial ongoing losses, of at least -£100m per year as an educated guess. For what it’s worth, Bentley probably wins the financial battle comfortably.

Of course, both are growing, and as noted previously have been growing faster than their owners as a whole, at high single digit CAGR for revenues and even higher profit growth. However both are yet to fully face the challenges of electrification, though BMW are arguably ahead of VW in technology for that (Volvo / Geely, via its Polestar brand, as a full high end EV performance car which serves as a template for what these two venerable names might look to).

Conclusion

Ultimately, the consensus seems to be that both sides got what they wanted out of these brands when they battled to acquire it in 1998. VW got a sporty brand that could scale, which it has done; BMW got a limousine brand which was not designed to be scalable but to really create a layer above its premium positioning. VW wanted the hard assets of the former business including the factory and staff, given the failure of Phaeton; BMW had most of its platform already available for use and could staff up its new Goodwood facility internally. That explained the difference in pricing – BMW spent £50m on the brand and then some £100m on building the new factory, compared with the £430m VW spent buying a going concern. Bentley is meaningfully profitable though, whereas Rolls Royce has yet to contribute financially.

What neither side anticipated then, but both reacted to, was the rise of the SUV, which perhaps suited the saloon platform better than a sport GT one. Each side has done well but RR has really taken off on its SUV offering; the EV challenge will be next. At the end of the day though, the real benefits will have to be chalked up to ‘intangibles’ including prestige for the owner and, one assumes, spillover benefits from any R&D linked to these luxury marques. It is probably really us, the consumer, who has benefited from these two auto giants deciding to maintain what are basically hobby horses; if the Germans were not so vain, we probably would not have the cars we enjoy today ….

Appendix