With the latest conflict now settling down to the usual name-calling and posturing, we are once again confronted with the insolubility of the Middle East problem. For those like myself who grew up with another version of this – the sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland and its impact on politics and society in the UK at large – this is all too familiar. And for myself, much as I felt with that episode of history, I cannot help but be bored each time it starts again, because there is actually no solution which will bring a lasting peace until, as with Northern Ireland, we start to move beyond political conceptions on which states and borders are based.

Before I get to my historical analysis however, I would also give a nod towards the issue of foreign observers and their inability to grasp real motivations of those on the ground. Graeme Wood made the point, during the rise of ISIS in 2015, that the hand-wringing in Washington and Brussels would never help until they acknowledged the underlying religious inspiration behind the Caliphate. People do genuinely act on matters of theology; it is not all (or even mainly) a matter of economics and the Marxist interpretations. But of course, western observers, whose political classes are by and large either atheist or at best agnostic, could never comprehend this and would therefore keep wanting to bring a knife to a gun fight. The naive but enduring hope that improving the economy and jobs would somehow solve the problem that Islam presents is really a problem of the observer, not the subject.

However to return to a more Realist angle, I have no interest in how to solve the current Palestinian problem, but I do have an interest in the historical provenance. Because like it or not, the Israel issue is one of several which have their roots in intellectual limitations of state-makers in the immediate aftermath of World War II, roughly from 1946-1954. We saw the same problems erupt as India gained independence and split between Hindu, Muslim and Sikh; and in the slower issues built up in the corners of China as Mao consolidated around the Qing Dynasty imperial borders. In every case, conflict and bloodshed were born of trying to fit the square peg of empire into the round holes of nation-statehood.

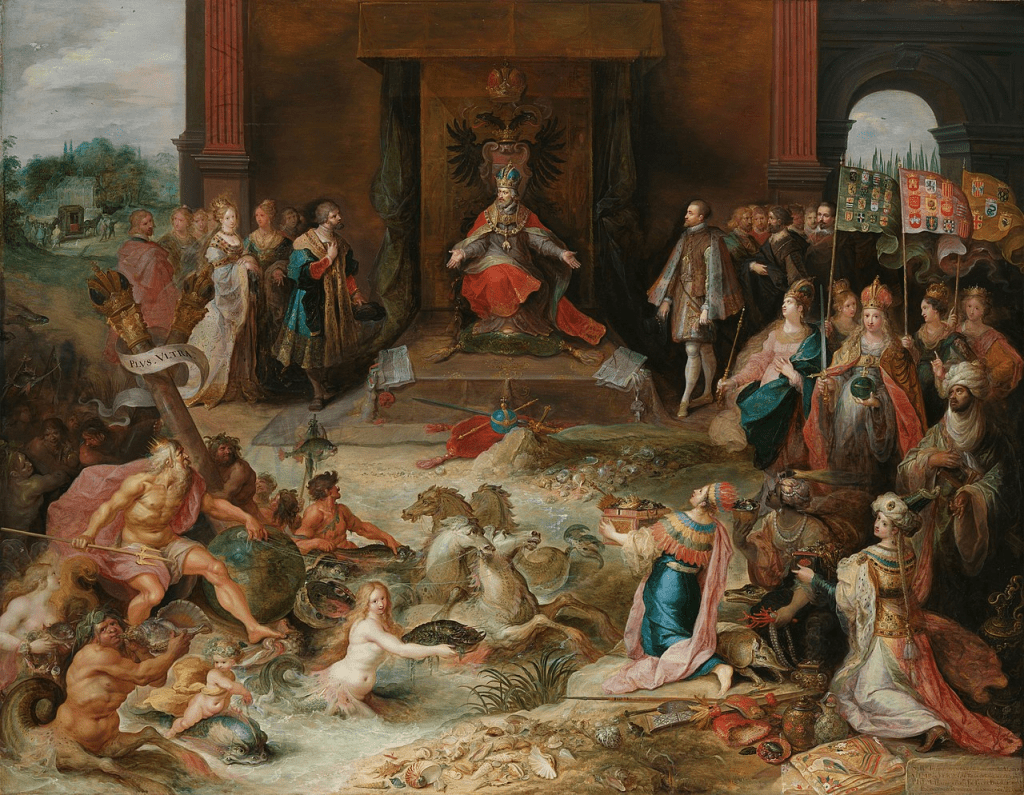

The ‘nation-state’ itself is, of course, a somewhat recent phenomenon. While it is a little trite to date them specifically to Westphalia in 1648, it is certainly true that a century earlier at the Peace of Augsburg, the connection between rulers and the ruled based on ethno-cultural identity was barely existent. The splendid Charles V, in his twilight in 1555, was the legitimate ruler of inheritances including Spain and the New World, Austria and the Holy Roman Empire, and Burgundy. Nobody on the streets of Vienna, Antwerp or Madrid complained about his ethnicity – even if they might complain about misrule. This detachment between where a ruler came from and his authority only changed with the advent of new weapons, increasingly expensive wars, and the compensation offered by rulers to their subjects for ever-higher taxes to fund the military. ‘Nationality’ was a part payment for the debt being incurred by princes as they required greater blood and treasure – “we need more from you, but you’re now fighting for your own people!”.

So nation-states, in other words, with their hard borders and inherent desire for ethnic, cultural, religious and linguistic cohesion, were a creation of European diplomacy just a few hundred years ago. And it served them fine, even as the rest of the world tended still towards the more nuanced and subtle lines of empire – today a byword for violence but in actual fact a creator of peace for most people. In simple terms, for instance, it made perfect sense for Tibet to exist within the Chinese imperial sphere; but made very little sense for it to be incorporated into a new Chinese nation-state. Likewise the Northwest Territories to the Raj. Most of all, in Jerusalem the centuries of occasionally tense but balanced coexistence between Arab, Jew and Christian was brought to an end with the creation of the Israeli state in 1947.

All three of these examples – and plenty of others besides – would have benefited from revolutionaries who looked past the (even then already dated) concept of European nation-statehood. In each case a forward-looking, more federalised concept of governance could easily have been introduced. In Europe itself, political leadership was looking at a post-national world which would lead eventually to the European Union. So why was none of this progressiveness around in Israel, India or China?

First is pure laziness. A vast number of unfounded charges are laid at the feet of the British Empire (which left the majority of its people better off than before), but the one criticism which sticks is the undignified rush to decolonisation, and the unintellectual approach used for it. Britain of course, as demonstrated with the EU, is in any case the wrong source of inspiration for ‘post-nationalism’, but at the time the navel-gazing was due to self-obsession. The credit for all the good that Empire brought, was more than a little diminished by the inglorious process of its end.

But the bigger issue was the lack of imagination from the heroes seeking to create new countries of China, India and Israel. Mao and Zhou, Gandhi and Nehru, Weizmann and Ben-Gurion were all leaders steeped in the orthodoxy of western historical teaching, and could conceptualise of nothing else other than the national structure of western powers (despite, ironically, the fact that those same imperial powers tended not to apply statehood in the empire, resulting in a measure of peace). When Churchill called Gandhi “a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir… striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceregal Palace” it was as much a comment about his cultural background as it was about his privilege. Gandhi suffered, as they all did, from a sort of Stockholm syndrome where because Europe comprised all nation-states, so should their newly independent post-imperial entities.

Not all such Westphalian myopia ended in disaster. A few successful examples included Lee Kwan-Yew’s establishment of Singapore, or the stability achieved for long periods in Thailand or Japan. But in general, the larger conflicts today still exist because someone, somewhere, could not get their minds around the temporary and cyclical nature of national constructs, instead pursuing hard-bordered strategies that had to end in bloodshed. They were not helped by their former masters, to be sure; but ultimately it is difficult for these founding fathers, all of whom played up their own supposed knowledge of history, not to take the majority of the blame.

The crises in Palestine and elsewhere, such as they are, are the fault of aspirant statesmen who could not think outside the box. None of them had a proper historical grounding, and generations since are paying for it. This insolubility deserves ennui, not obsession.