An absurd online tussle has commenced over Allan Lichtman’s ‘Thirteen Keys’ thesis over the coming US presidential elections, where not only are endless amounts wasted on challenging his predictions (“He is biased! No he’s not! He’s pro-Democrat! He wears a wig!” etc), but actually being threatening to the poor septuagenarian. Even in the heated environment of this contest, as JD Vance says, this is not worth it.

Yet it presents a good opportunity to think about how robust his model actually is. For the record, I like this type of macro historical analysis, and I think it has value. In particular I like the discipline it instils in not subjecting the election only to the noise of the latest polling. On the other hand, I have a sneaking suspicion (famous last words, perhaps) that Lichtman’s actual predictions this year, which are for a Harris victory, may be wide of the mark. Would this render the model broken?

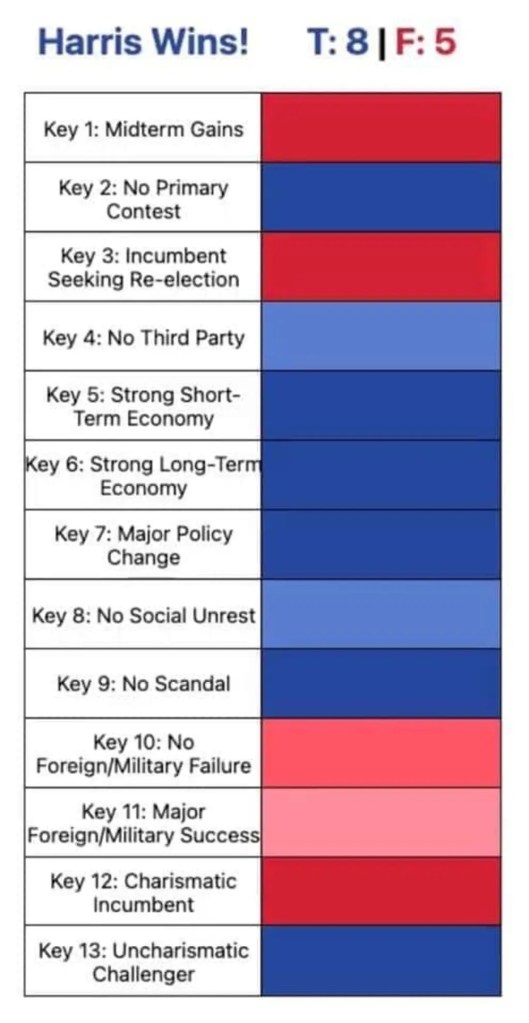

I don’t think so. Trump may well win this year, but if he does so it will be less about Lichtman’s model being wrong so much as Lichtman’s own interpretation of it. Let us bear in mind that the model is just that – a neutral series of tests (explained in detail here) – but Lichtman then has to take these tests and package them into an opinion (below is the most recent I can find). There is plenty of room for subjectivity. Currently, he sees the lie of the land like this:

Critics of Lichtman’s model – and there have been many – mainly focus on the keys that are obviously open to interpretation and are therefore ‘subjective’. Nate Silver for instance notes that the two “charisma” tests are very much in the eye of the beholder, while others would complain that the definition of a “major policy change” or foreign policy “success” or “failure”.

However I am less interested in those tests so much as the supposedly binary ones. Because the problem is that the whole political system has been shaken in the last decade, resulting in what I think are some structural problems in Lichtman’s definitions – his underlying intent is correct but the manifestation of the issue he has identified no longer conforms to how he has set the keys up. Below, I focus on a few examples.

Key 2: No primary contest

Now this may seem obvious and technically true, but I think Lichtman may not be seeing the wood for the trees this year and ignoring his own wisdom. If we take a step back, the point of there being “no primary contest” is essentially that the incumbent party has not had a bruising encounter which exposes disunity in the ranks of the incumbent party seeking re-election (apparently the same is not true for the opposition, which I have some sympathy with).

But considering what has occurred in 2024, I am not clear that this is true in spirit, even if it by letter. The fact is that many Democrat supporters either a) resented Biden being deposed the way he was, or b) did not like Kamala’s unchallenged rise to the nomination. I personally know a few who have not forgiven the party for what appears to have been a hugely opportunistic change (and let’s be clear, it was perfectly possible to have still had some sort of debate leading up to the Convention, something championed by many including Ezra Klein and numerous others here and here). While Harris acceded unopposed at the Convention, her elevation left quite a bitter taste in many corners of the party.

Thus, while technically the incumbent party did not have a divisive primary, there has in fact been discontent around the selection procedure, so awarding the key to the Democrats in this case is structurally dubious.

Key 3: Incumbent seeking re-election

In this case Lichtman has given a key to Trump which is questionable. Of course, again strictly speaking, Harris has not been President and is therefore a new candidate. And even allowing for sitting VPs such as Al Gore not being considered ‘incumbent’, the peculiar issues surrounding 2024 again makes this seemingly binary key more nuanced.

Is Harris an incumbent? Who is the incumbent? Not only has Harris been part of a long-running trend whereby VPs have been more active in the Executive (Gore and Cheney, and now Harris), but she has now basically been Acting President due to Biden’s incapacitation. She was elevated only after the incumbent had been selected and had started to campaign for the presidency; she has inherited almost his entire infrastructure and strategy and by choice or not, has been unable to distance herself from the Biden administration. To my mind, unlike when a VP runs after an 8 year term (such as Gore in 2000, or HW Bush in 1988), I think the public will likely see Harris as a continuity of the regime, for better or ill. In Lichtman’s model she should therefore get credit for more or less being an incumbent.

Key 4: No third party candidate

Here is perhaps the most far-reaching and controversial challenge to Lichtman’s definitions. Again, of course, this is technically true since Lichtman defines “third party candidate” to mean an officially non-aligned candidate who polls more than~5% of the popular vote. In other words he is limiting himself to the Ross Perots and Barry Goldwaters of electoral history. But with 2016, I think this part of the model has been completely blown out of the water.

Trump, in 2016, was essentially the first third party candidate to win the presidency. Yes, he ended up tackling the Republican primary and using that as a vessel into politics, but he famously had previously been a Democrat and moreover, disagreed with much of the incumbent GOP platform and heritage. Trump’s greatest moment in the primaries was arguably his anger at calling out the Republican establishment over the Iraq War, and being roundly booed for his troubles:

To look at the purpose of Lichtman’s key, it exists to highlight that a significant third party usually indicates discontent with the system, which tends to favour the challenger (this I think is a debateable point but generally I can understand his perspective). No third party therefore favours the incumbent. Yet if a challenger has essentially captured the opposition vessel for effectively becoming a third party candidate, this no longer applies. The same would be true, back in 2016, of a potential Sanders candidacy for the Dems would have seem him as an outsider also. I previously expressed the 2016 worldview like this:

So ultimately we are judging Lichtman’s model by his own narrow interpretation, since as far as I know nobody else is doing an independent version using the same system. But just as an example, if I switched the three examples above around, the 8/5 balance becomes 7/6, and we would be left with discussions over imponderables such as the fact that there are millions of Obama-Trump voters, which belies the thinking that Trump does not win over people from the other side (the definition of “charistmatic challenger”). Indeed whether Trump, in or out of power, would ever be not a “challenger” is itself a question for Lichtman.

For the record, my own interpretation of the Lichtman model offers a 8/5 in favour of Trump. In addition to the key changes above, I would change the charismatic challenger key as explained, and I also sense the “scandal” key to be more prominent than Lichtman believes, because I think there is a whiff of wrongdoing around how long or how early senior Democrats have been hiding Biden’s senile incapacitation. But, as others have noted, these are down to personal views and the polls continue to tell us the race is close.

On balance, I would say that Lichtman’s model is one which we can proceed with with caution for fun, but I would urge psephological geeks (such as myself) to drill into the underlying keys and render their own interpretation, rather than rely on Lichtman’s. Separate the man and his keys, and you may be better off.